Therefore, a sentence such as, “I miss not hearing your voice,” implies that you would prefer the person stay quiet. If you were to say, “I hadn’t barely gotten out of the shower when the phone rang,” it might imply that you were showering with your clothes on.Īnother example of a word with a covert negative element is the verb “miss.” If you miss something or someone, it implies that the person or thing is not present. It is important to pay attention to this type of double negative and try to avoid it. It would make more sense to say, “I had hardly gotten out of the shower when the phone rang.” For example, if you said, “I hadn’t hardly gotten out of the shower when the phone rang,” it would be a bit much for your audience to process. These are words such as “barely,” “hardly,” and “scarcely.” When words with a negative affix are used with words such as these that have negative elements, they come across as redundant and clunky. Then there are words that are understood to have a negative element, even though they have no negative affix expressly identifying them as such.

If we apply the conventional rules to my second sentence, “Nobody ever did nothing for me,” am I saying that somebody did something for me, or everybody did everything for me, or everybody did something for me, or somebody did everything for me? You can start to see why this kind of construction gave your English teacher fits. Thus, the two negatives form a positive and the actual meaning of the sentence is, “She did see something,” which is the complete opposite of the intended meaning.Īnother argument against using this type of double negative is that it results in a sentence that is confusing or ambiguous. We all know that when someone says, “She didn’t see nothing,” what they mean is, “She didn’t see anything.” However, conventional wisdom says that when someone says something like, “She didn’t see nothing,” the two negatives cancel each other out, as they would in multiplication. These are the double negatives that really drive English teachers crazy, and as a former teacher myself, I have to admit that they are not my favorites either. When double negatives use words such as these, we end up with constructions such as the following: Most of them begin with the affix “no”:Īdditionally, even though they don’t have “no” in them, you can still tell that words such as “neither” or “never” are negative without a great deal of analysis. There are some words or phrases that you can tell are negative without even looking at them very hard. Double negatives come in three different flavors.

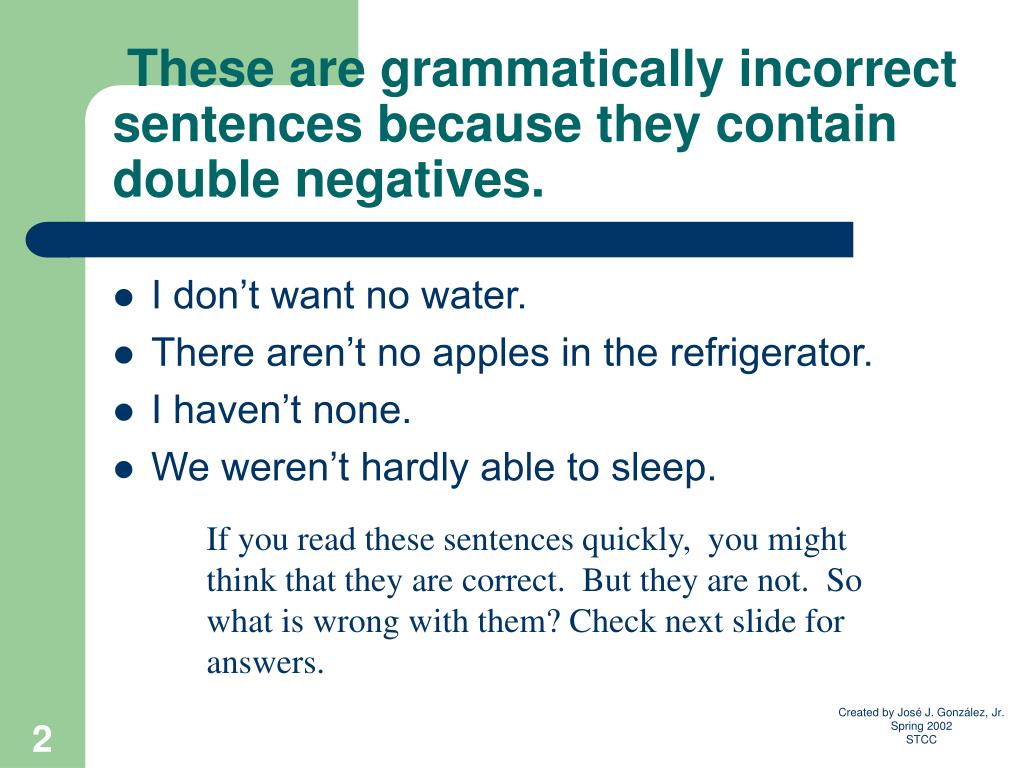

The basic definition of a double negative is a clause that contains two negative words. However, it is not appropriate for every situation. It’s not incorrect to use a double negative, as I did just now. Nevertheless, in researching this article, I found out that there are still a lot of grammar snobs out there who insist that a double negative is not grammatically correct. So did Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare. Douglas Adams in The Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy: "plastic cup filled with a liquid that was almost, but not quite, entirely unlike tea.Have you ever used a double negative in your writing? If so, you are in good company. Chaucer makes use of double negatives to describe characters, such as the Friar, in The Canterbury Tales: "There never was no man nowhere so virtuous."ģ. Shakespeare's Twelfth Night uses a triple negatives in the following line: "And that no woman has nor never none Shall mistress of it be, save I alone".Ģ. (This might be a time when a double negative is needed-"I" doesn't want to say that he cares, but also doesn't want to say he doesn't care.Įxamples of Double Negatives in Literatureġ. (If you did not know neither of them, then you must know both of them.)ĥ. I did not know neither the date nor the month. (This might be a time when a double negative is needed-the person doesn't want to say he is "attractive," but also doesn't want to say he's not "attractive".)Ĥ. (If she didn't see "nothing," she must have seen "something.")ģ. (If you don't want "nothing," you must want "something.")Ģ.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)